What was once dismissed as the food of the poor is now the star of high-end restaurants and luxury grocery shelves across India. On December 25, 2022, in Bhopal, a quiet culinary revolution was documented: millet, the humble, drought-resistant grain long associated with rural poverty, had become a status symbol on the plates of India’s urban elite. The twist? It wasn’t just a trend—it was a national policy success story, backed by science, politics, and global recognition.

The Great Grain Reversal

For generations, bajra, jowar, ragi, and other coarse grains were staples in the diets of India’s poorest, especially in drought-prone regions like Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. They were cheap, filling, and resilient—but socially stigmatized. "They were the food you ate when you had nothing else," recalls Dr. Anjali Mehta, a food anthropologist at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Now, those same grains are being sold as organic superfoods in Delhi’s premium supermarkets, priced at double the cost of white rice.

The shift didn’t happen by accident. In 2023, the United Nations General Assembly declared the year as the International Year of Millets, a move that gave global legitimacy to a crop long ignored by mainstream agriculture. But the real engine of change was domestic. Since 2014-15, the Government of India quietly pivoted its agricultural strategy toward millets—not just for nutrition, but for climate resilience and farmer income.

Policy, Science, and the Rise of a New Food Economy

It wasn’t until agricultural research centers across India—like the Indian Council of Agricultural Research in Hyderabad—published peer-reviewed studies showing millets’ superior nutritional profile that public perception began to shift. These grains contain more iron, calcium, and fiber than rice or wheat. They’re gluten-free, low-glycemic, and help regulate blood sugar. Suddenly, diabetes patients, fitness influencers, and yoga retreats were all pushing millet khichdi.

By 2023, the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare had launched a cascade of initiatives: subsidies for millet farmers, procurement guarantees, and even mandatory inclusion of millet in mid-day meals across 11 states. The result? Millet production rose 47% between 2018 and 2024, according to PIB data from October 2025. New startups emerged—Millet Magic in Bengaluru, Ragi Roots in Pune—selling millet cookies, pasta, and even millet-based energy bars.

"We used to sell 500 kg of ragi flour a month," says Suresh Patel, a grain merchant in Indore. "Now we sell 12 tons. And half of it goes to luxury hotels in Mumbai and Bangalore. The rich don’t just eat it—they post it on Instagram with hashtags like #MilletsAreTheNewSuperfood.""

The Irony of Food Security

Here’s the bitter irony: while the affluent rediscover millets as a wellness trend, the very communities who once relied on them for survival are now being pushed out of their own food system. The National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 was designed to feed 813.5 million people—75% of rural and 50% of urban India—through subsidized grains. By October 2025, 789 million beneficiaries were covered under NFSA, supported by programs like Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) and the Work-Centered Purchase Scheme (DCP).

But here’s the catch: the NFSA still primarily distributes rice and wheat. Millets, despite their nutritional superiority, are not yet a mandatory component. That’s changing slowly. In Maharashtra, the Shiv Bhojan Thali scheme—relaunched in November 2025 with ₹70 crore—offers a ₹10 meal of rice, vegetables, and two rotis to daily wage workers. Yet, even this program uses wheat rotis, not millet ones.

"The government wants millets to be profitable for farmers," says Dr. Priya Nair, a food policy analyst at the Centre for Science and Environment. "But they’re not yet prioritizing it as a food security tool for the poor. That’s the disconnect. The rich get the superfood. The poor get the same old grain, just at a lower price."

What’s Next? A National Plate Reimagined

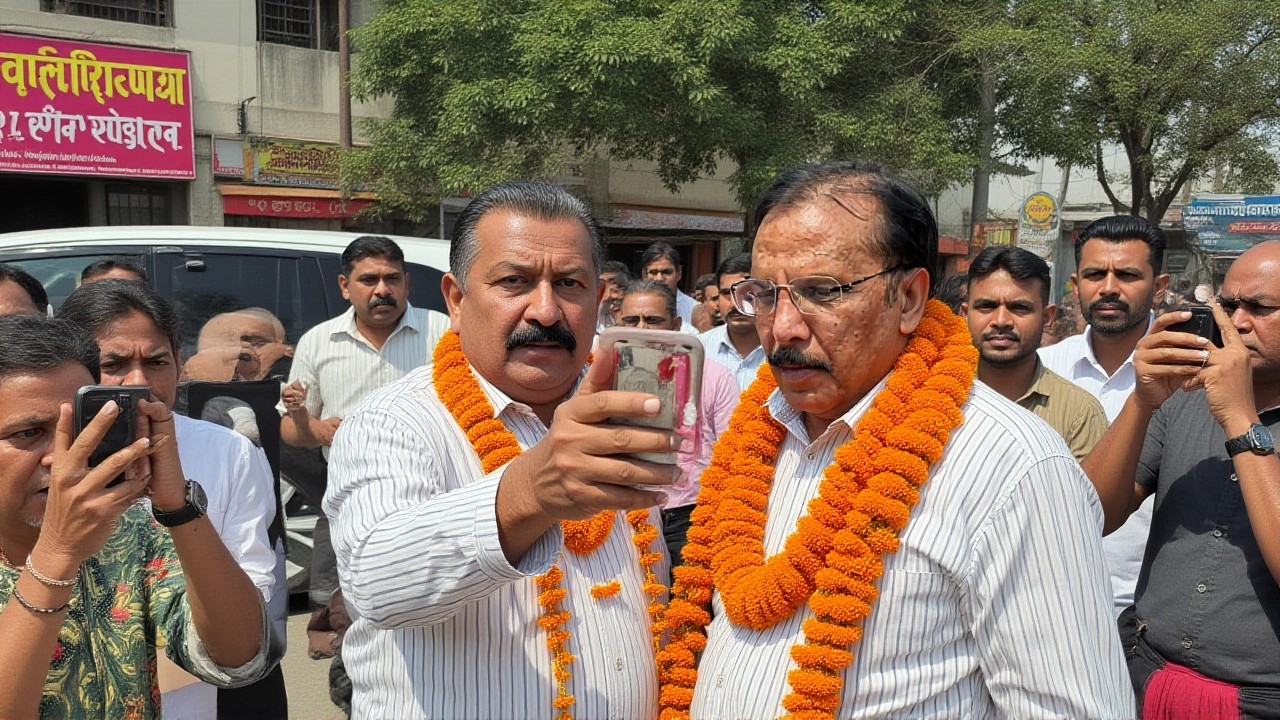

The Shri Narendra Singh Tomar, India’s Central Agriculture and Farmers Welfare Minister, made it clear at the Agriculture Leadership and Global Nutrition Conference that millets are no longer niche. "This isn’t about fashion," he said. "It’s about food sovereignty, climate adaptation, and rural prosperity."

By 2026, the government plans to integrate millets into the Public Distribution System (PDS) on a pilot scale in five states. The Krishak Jagat editorial from December 2022 captured the essence: "Coarse grains used to be consumed by low-income and poor people some decades ago, but have now become the pride of the plates of the rich."

The transformation is complete. Millets have shed their stigma. But the question remains: will they lift up the poor who first nurtured them—or just enrich the elite who now market them?

Background: A Grain’s Journey Through Time

Millets have been cultivated in India for over 5,000 years. Archaeological evidence from the Indus Valley Civilization shows millet grains stored in granaries. They were the backbone of pre-colonial diets. But during British rule and after independence, green revolution policies favored water-intensive rice and wheat. Millets were pushed to the margins—cultivated only in rain-fed, remote areas.

The 2014-15 policy shift marked the first time the government treated millets not as a relic, but as a strategic asset. Soil degradation in states like Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh made millets attractive again—they grow in poor soil, require little water, and improve land fertility. Farmers in Odisha and Chhattisgarh saw their incomes rise by up to 30% after switching from cotton to finger millet.

By 2023, the global market for millet products had grown to $2.3 billion, with India accounting for 65% of production. Countries like the U.S. and Germany began importing Indian millets for gluten-free product lines. Meanwhile, in rural India, women’s self-help groups started processing and branding millet flour locally—bypassing middlemen entirely.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are millets suddenly considered "superfoods" when they’ve always been nutritious?

It’s not that millets became healthier—they’ve always been rich in iron, calcium, and fiber. What changed is visibility and marketing. Research from ICAR and other institutions in the early 2020s validated their health benefits, which were then amplified by influencers, wellness brands, and government campaigns. The UN’s 2023 designation gave them global credibility, turning a traditional crop into a modern trend.

How has this shift affected small farmers?

For many, it’s been transformative. In states like Telangana and Rajasthan, millet farmers now earn 25–40% more than those growing rice or wheat, thanks to government procurement at minimum support prices and direct contracts with private brands. However, smallholders without access to storage or processing units still struggle to benefit. The real winners are agri-startups and large cooperatives that can scale.

Is the government including millets in food security programs for the poor?

Not yet systematically. While the NFSA covers 789 million people, it still primarily distributes rice and wheat. Millets are being piloted in mid-day meals in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, but not yet in the PDS. Advocates argue this is a missed opportunity—millets could combat anemia and diabetes among the poor more effectively than rice. Policy inertia and supply chain gaps remain barriers.

What’s the difference between millets and the grains still given under PMGKAY?

PMGKAY provides rice and wheat—both highly processed, low-nutrient staples that contribute to metabolic diseases in the long term. Millets, by contrast, are whole grains with high micronutrient density. Switching even 20% of rice rations to millets could reduce anemia rates among women and children by up to 18%, according to a 2024 study by the Public Health Foundation of India. The cost difference is negligible, but the political will is still lacking.

Why did Maharashtra relaunch the Shiv Bhojan Thali scheme in 2025?

The scheme was paused in March 2025 due to budget cuts by the Mahayuti government, but relaunched ahead of local elections with ₹70 crore in funding. It targets daily wage workers and migrants by offering a ₹10 meal. However, it still uses wheat rotis and rice—not millets. The relaunch was more political than nutritional, aimed at regaining voter trust rather than improving dietary quality.

Will millets replace rice and wheat in India’s diet?

Not replace—but complement. Experts predict millets will make up 15–20% of India’s staple grain consumption by 2030, up from less than 5% today. Cultural preferences for rice and wheat remain strong. But with climate change reducing water availability and rising health concerns, millets are becoming a necessary part of the mix—not a luxury, but a lifeline.